At the beginning of his first term in office in 2019, Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi vowed to make his country “the Germany of Africa”.

He promised to grow the economy and create jobs for the people, in a country with massive resources but whose population was living in poverty.

In his first four years in power, he did not achieve his ambitious goal of transforming such a vast country, but now he has a second chance after he was declared the winner of a chaotic election. He is due to be sworn in for a second term on 20 January.

Mr Tshisekedi first came into power in unusual circumstances.

He was declared the surprise winner of a disputed presidential election, which some, including the influential Catholic Church, had challenged.

His main rival Martin Fayulu alleged that outgoing President Joseph Kabila had engineered a secret deal for Mr Tshisekedi to succeed him – charges that were strongly denied.

Mr Fayulu and other opposition candidates have also said the 2023 election was marred by fraud and demanded a rerun. The electoral commission has dismissed such claims as sour grapes.

Until a few years before the 2018 election, Mr Tshisekedi was largely untested in high-level DR Congo politics.

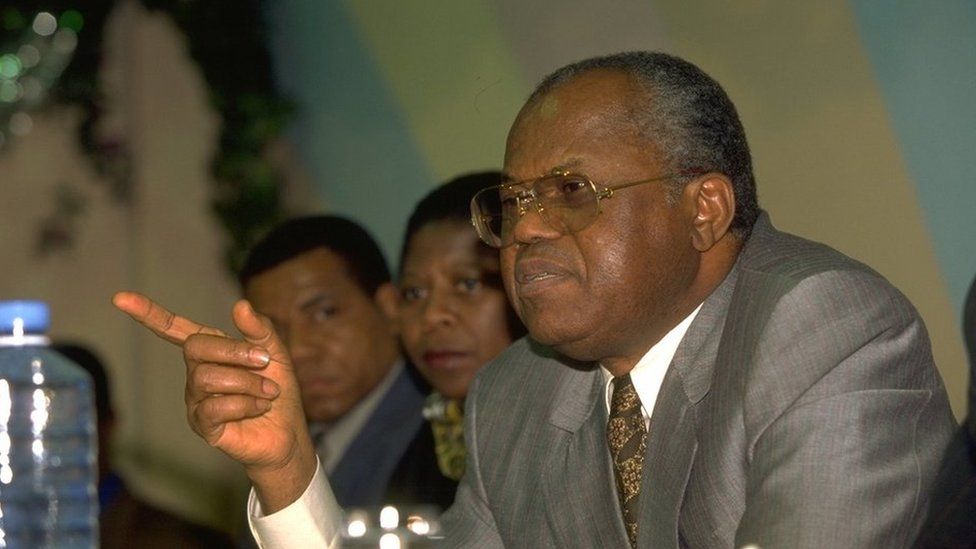

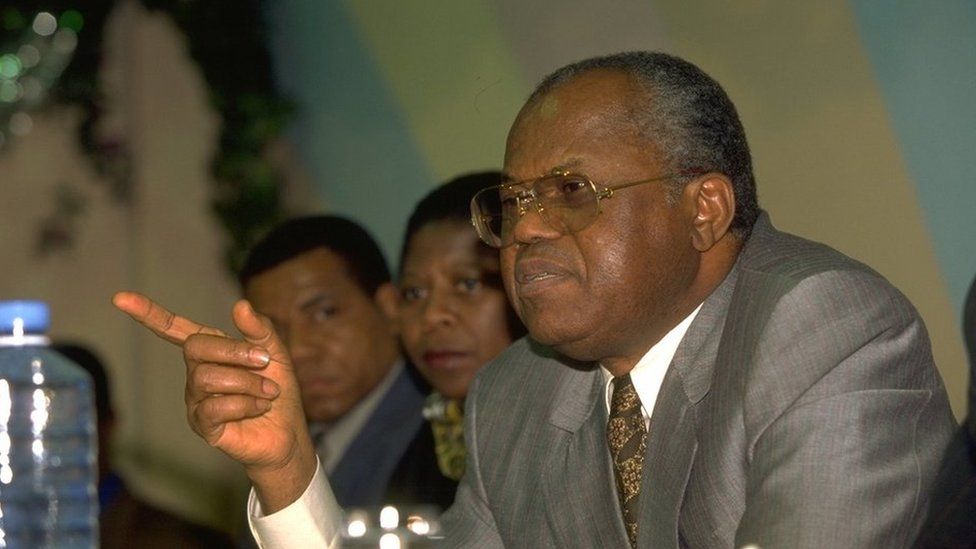

He was more known for who he was related to – he is the son of the veteran late opposition leader Étienne Tshisekedi.

He however did not simply cash in on his father’s name and was immersed in politics from a very young age, and worked his way up through the party ranks.

He also had to suffer the consequences of his father’s political activism.

When Tshisekedi senior founded the Union for Democracy and Social Progress party (known by its French initials UDPS) in 1982, the family was forced into internal exile in their home town in the central Kasai province.

Étienne Tshisekedi founded the UDPS in 1982, turning it into the country’s largest opposition party

They stayed there until 1985, when Étienne Tshisekedi’s long-time rival, autocratic leader Mobutu Sese Seko, allowed the mother and children to leave.

Félix Tshisekedi then moved to the Belgian capital, Brussels. After completing his studies there he took up politics, working his way through his father’s party to become national secretary for external affairs for the UDPS.

His father’s former chief of staff, Albert Moleka, told the BBC in 2019 that Mr Tshisekedi “made powerful friends and allies among the diaspora there, but he was sometimes overlooked – and so it wasn’t easy for him”.

Mr Tshisekedi’s inauguration in 2019 inspired some hope, as it was the first peaceful transition of power in the country since independence in 1960.

At his swearing-in ceremony, he told the crowds that he wanted to “build a strong Congo, turned toward development in peace and security – a Congo for all in which everyone has a place”.

Mr Tshisekedi said he would make the fight against poverty a “great national cause”, reduce unemployment and tackle corruption.

In his first term, President Tshisekedi introduced free primary schooling, with enrolment increasing by more than five million students.

The programme has however been criticised for the overcrowding of classrooms in some areas, while teachers remain poorly paid.

The president also introduced free health services for mothers giving birth in preselected heath centres and hospitals in the capital, Kinshasa, which he has promised to extend to the rest of the country if he is re-elected.

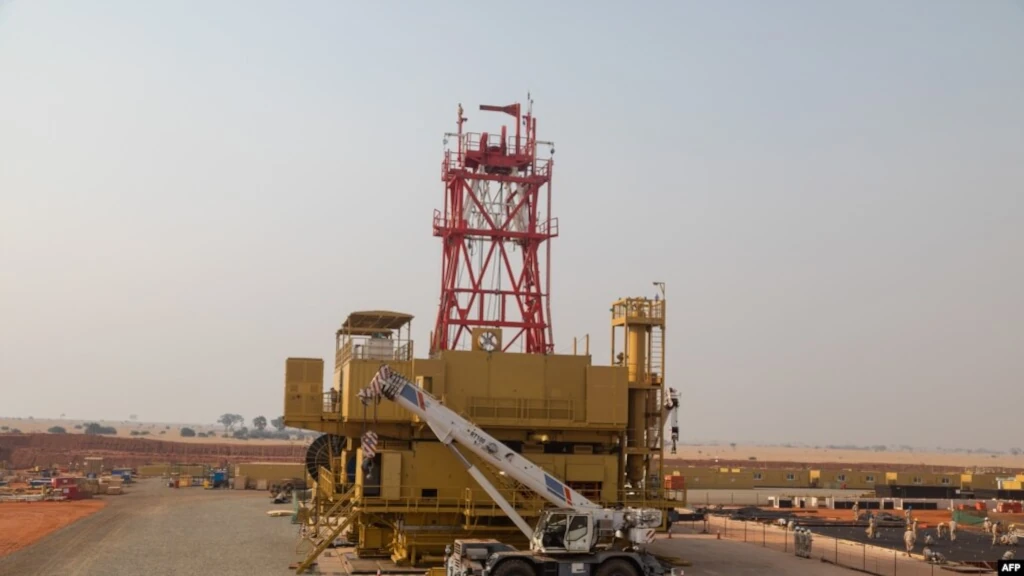

He has pushed for a review of the country’s mining contracts with China so it can keep a larger share of its vast mineral wealth.

In a state of the nation address last month, he said the economy had improved, with the national budget having grown nearly three-fold from $6bn (£4.7bn) at the beginning of his tenure to $16bn this year.

We have come a remarkable way since 2020, overcoming the challenges posed by the pandemic to achieve rates of economic growth that inspire confidence in the future,” he said.

In spite of the growth, many Congolese have been complaining about the depreciation of the Congolese franc which is having a serious impact on their daily lives.

Despite its vast mineral wealth and huge population, life has not improved for most people, with conflict, corruption and poor governance persisting.

In his re-election campaign, he made some of the same promises he made five years ago, such as creating more jobs, making the economy more resilient and promising to tackle the insecurity that has wracked the east of the country for three decades, leading to the deaths of millions of people.

Mr Tshisekedi’s supporters point to his investment in schools and healthcare

Much of the country’s natural resources lie in the east where violence still rages despite Mr Tshisekedi’s attempts to deal with the situation by imposing a state of siege, ceasefire deals and bringing in regional troops.

These included a force from the East African Community, which DR Congo joined last year, hoping to improve trade and political ties with its eastern neighbours.

However things have not worked out as planned and Mr Tshisekedi has ordered them to leave, saying they had been ineffective. He has said he wants to replace them with troops from a different trade bloc of which DR Congo is also a member – the Southern African Development Community (Sadc).

But there is little sign of them coming any time soon.

Mr Tshisekedi has also demanded the end of the UN peacekeeping mission in DR Congo. After more than two decades, it will take some time for the thousands of troops to leave, but it has raised fears of a security vacuum as the army is in no position to take on the numerous rebel groups which operate across eastern DR Congo on its own.

DR Congo’s membership of the EAC is complicated by the fact that Mr Tshisekedi, as well as UN experts, say fellow member Rwanda is backing one of the most active rebel groups in eastern DR Congo, the M23.

Rwanda’s government has strongly denied this but it has led to a souring of relations between Mr Tshisekedi and his Rwandan counterpart, Paul Kagame, that has defined the end of his first term.

It was not always that way. At the beginning of his term, Mr Tshisekedi initially tried to mend relations with neighbouring countries including Rwanda.

In a surprise gesture, he invited President Kagame to the funeral of his father in May 2019.

In the latter years of his presidency, however, the relationship has become so frosty that Mr Tshisekedi recently compared Mr Kagame to Germany’s World War Two dictator.

While addressing a campaign rally in Bukavu, close to the Rwandan border, Mr Tshisekedi last week said of Mr Kagame: “I promise he will end up like Adolf Hitler.”

Hitler, responsible for the deaths of millions, including six million Jewish people in the Holocaust, ended up taking his own life in a bunker in the German capital, Berlin, in 1945.

The Rwanda’s government described the Congolese president’s comments as “a loud and clear threat”.

In his final rally before the election, he even vowed to declare war on Rwanda if he was re-elected. While he was hoping to whip up nationalist sentiment, most Congolese will be hoping he does not follow through on this pledge.

They would prefer him to stick to his previous goal of creating jobs and transforming the economy, even if turning the country into the “Germany of Africa” remains a distant dream.

Source: BBC, 31st December 2023

afric-Invest

afric-Invest