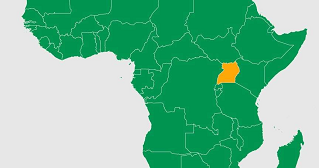

The Board of Directors of the African Development Bank (AfDB) Group approved a loan of $252.83 million to Uganda, to fund the construction of the Laropi-Moyo-Afoji and Katuna-Muko-Kamuganguzi road.

The financial support consists of two loans: $179.68 million from the African Development Bank and $73.15 million from the African Development Fund, the Bank Group’s concessional loan window. “The Laropi-Moyo-Afoji/Katuna-Muko-Kamuganguzi road project is intended to improve rural transport connectivity and facilitate regional integration in the districts of Kabale, Rubanda, and Moyo, in Uganda. It will boost incomes, deepen regional integration, and facilitate trade while opening up an alternative transport corridor linking Uganda with South Sudan,”, said Augustine Ngafuan, the African Development Bank’s Country Manager in Uganda.

“Building this infrastructure will enable economic operators along this route to reduce costs and lead times while improving the efficiency of transport logistics,” added Mr. Ngafuan.

In addition to the two main roads, the project will also support the following social complementary initiative: 5 kilometres of roads in small towns and non-motorized traffic facilities (walkways and cycle tracks) within Moyo and Laropi in northwestern Uganda to improve mobility; street lighting to improve the business environment for traders, and regional bus terminus in Moyo.

The project also provides for the construction of market stalls complete with cold storage facilities in Kashasha/Katuna, Moyo and Laropi to support women traders who currently operate on the roadsides, in order to improve earnings from perishable products such as fish and vegetables.

There will also be flood protection works in Laropi to strengthen resilience to the effects of climate change and reduce disruptions to commercial activities. Lastly, a one-stop border post will be constructed in Afoji/Jale on the Uganda-South Sudan border to boost trade and transport activities and facilitate the harmonization customs and coordination of the border-crossing operations and supply chains.

The Laropi-Moyo-Afoji road is located in northwestern Uganda, in the district of Moyo, which has a population of about 140,000. Some 80% of the district’s land is arable and suitable for agriculture and horticulture. The Western Nile sub-region currently hosts more than 500,000 refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan. The road will provide vital access to several refugee camps and support agricultural communities in Kabale and Rubanda districts, with a combined population of about 460,000 inhabitants.

As of November 2023, the African Development Bank Group’s active portfolio in Uganda comprised 23 projects with a total commitment of $1,957 million.

Source: New Business Ethiopia, 2nd December, 2023

The Board of Directors of the African Development Bank (AfDB) Group approved a loan of $252.83 million to Uganda, to fund the construction of the Laropi-Moyo-Afoji and Katuna-Muko-Kamuganguzi road.

The financial support consists of two loans: $179.68 million from the African Development Bank and $73.15 million from the African Development Fund, the Bank Group’s concessional loan window. “The Laropi-Moyo-Afoji/Katuna-Muko-Kamuganguzi road project is intended to improve rural transport connectivity and facilitate regional integration in the districts of Kabale, Rubanda, and Moyo, in Uganda. It will boost incomes, deepen regional integration, and facilitate trade while opening up an alternative transport corridor linking Uganda with South Sudan,”, said Augustine Ngafuan, the African Development Bank’s Country Manager in Uganda.

“Building this infrastructure will enable economic operators along this route to reduce costs and lead times while improving the efficiency of transport logistics,” added Mr. Ngafuan.

In addition to the two main roads, the project will also support the following social complementary initiative: 5 kilometres of roads in small towns and non-motorized traffic facilities (walkways and cycle tracks) within Moyo and Laropi in northwestern Uganda to improve mobility; street lighting to improve the business environment for traders, and regional bus terminus in Moyo.

The project also provides for the construction of market stalls complete with cold storage facilities in Kashasha/Katuna, Moyo and Laropi to support women traders who currently operate on the roadsides, in order to improve earnings from perishable products such as fish and vegetables.

There will also be flood protection works in Laropi to strengthen resilience to the effects of climate change and reduce disruptions to commercial activities. Lastly, a one-stop border post will be constructed in Afoji/Jale on the Uganda-South Sudan border to boost trade and transport activities and facilitate the harmonization customs and coordination of the border-crossing operations and supply chains.

The Laropi-Moyo-Afoji road is located in northwestern Uganda, in the district of Moyo, which has a population of about 140,000. Some 80% of the district’s land is arable and suitable for agriculture and horticulture. The Western Nile sub-region currently hosts more than 500,000 refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan. The road will provide vital access to several refugee camps and support agricultural communities in Kabale and Rubanda districts, with a combined population of about 460,000 inhabitants.

As of November 2023, the African Development Bank Group’s active portfolio in Uganda comprised 23 projects with a total commitment of $1,957 million.

Source: New Business Ethiopia, 2nd December, 2023

afric-Invest

afric-Invest